Friday 25 July 2014

Book Review: Private India by Ashwin Sanghi and James Patterson

Well known Indian thriller writer Ashwin Sanghi has teamed up with internationally acclaimed writer James Patterson to bring Patterson’s Private series to India. Private India ticks all boxes required of a thriller. It has a number of two-dimensional characters who could have been picked out from or planted in any other thriller. Pakistan’s ISI makes an appearance, as does a Mumbai underworld don, gold rings on various fingers and all. It has a couple of big mysteries and a few minor small ones. Most important of all, it is unputdownable and definitely a page-turner. Yes, one is forced to keep reading till the end, though the end is over 450 pages away.

Private India is India’s biggest and best detective agency, a branch of Private Worldwide, run by the inimitable Jack Morgan. Santosh Wagh heads Private India, though in this novel, Jack Morgan makes a few appearances and has a substantial role. When visiting Thai surgeon Kanya Jaiyen is killed in mysterious circumstances at the Marine Bay Plaza, Private India gets to the scene first since apparently it is employed by Marine Bay Plaza. The police come by later, but they are happy to let Private India get on with it, since they are overworked and have their hands full. The rule is the same as in countless other crime thrillers – the actual detective work is delegated to the private detectives on the understanding that if they succeed, the police will get all the credit. It is not clear who’s paying Private India to spend so much time and money on the hunt, but I didn’t let that get in the way of enjoying this fine thriller.

The first murder is followed by many others. Afternoon Mirror reporter Bhavna Choksi is the second victim. Then Elima Xavier, a school headmistress, Anjana Lal, the Chief Justice of Mumbai High Court, Ragini Sharma, a politician and others follow. The serial killer keeps killing without a break, each murder victim found strangled with a yellow scarf and surrounded by strange religious and cultural artifacts. Private India is unable to find the killer till a number of victims have fallen prey, but when it does, it does so in style, like any good thriller.

Like all good thrillers, Private India is not restricted to a main plot. In addition to the main plot – the identity of the serial killer, we get to know that Pakistan, acting through the Indian Mujahideen is trying to blow up the offices of Private India since Private India has thwarted so many of its plans and plots. Then there are minor mysteries such as why Police Chief Rupesh is no longer so well disposed towards to his old friend Santosh. Naturally all of these are resolved towards the end.

Since the novel is set entirely in Mumbai, I came across familiar landmarks in almost every chapter. From the Taj Hotel to Colaba and Haji Ali, to suburbs like Bandra, Andheri and Thane to the Tower of Silence and its vultures, Arthur Road Jail, Chowpatty Beach, Cooper Hospital, Private India is wrapped up with the sights, sounds and smells of Mumbai. Private India has detailed descriptions of advanced technologies used by Private India as well as explanations for complicated stuff like DNA evidence. All of this is done very well, on par with any Tom Clancy novel.

The only negative I found is that the English slips occasionally. For example, in one place one reads “that boy needs his beard trimming” instead of “that boy’s beard needs trimming”. Before I nitpick any more, let me stop by saying that despite such minor irritants, Private India is an excellent read.

Wednesday 23 July 2014

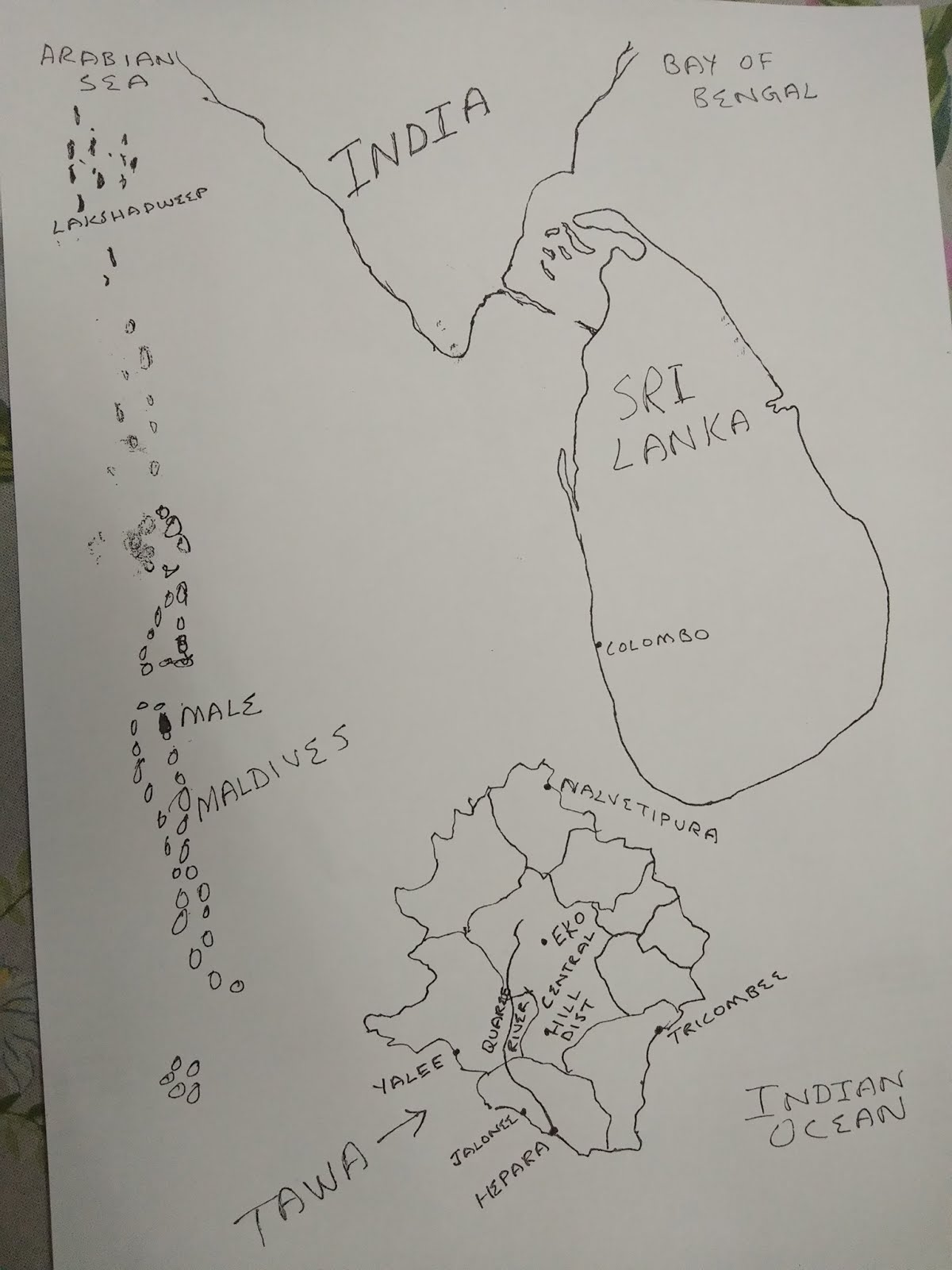

Book Review: This Divided Island – Stories from the Sri Lankan War, by Samanth Subramanian

At the Kangu Garage in post-war Jaffna, a few mechanics are hard at work. They don’t talk much to each other. All of them are in their 60s and 70s, as are almost all cabbies in Jaffna since most young Tamil men living in the North have been devoured by the cruel war. Chief Mechanic Nirmaladevan focuses on his work with such concentration that he is oblivious to his surroundings and to journalist Samanth Subramanian who stands nearby watching the men work. Samanth has made many visits to Kangu Garage and spent many hours waiting, hoping to strike up a conversation with Nirmaladevan and get him to talk about life during the war. Samanth has turned up in the morning before the mechanics arrive, during their lunch break and other odd hours, but Nirmaladevan has always managef to fob him off, pleading work pressure, focusing on his work with ferocious concentration in the placid calm of Jaffna where nothing really seems to be urgent. The only bit of information which Samanth manages to pry out of Nirmaladevan is that in 1995 they were forced to close down Kangu Garage when the Tigers, on the verge of ceding control of Jaffna to the Sri Lankan army, tried to persuade all civilians in Jaffna to follow them into Vanni wilderness. Unlike in 2009 when they successfully managed to force a few hundred thousand civilians to follow them to their final redoubt in Puthukkudiyiruppu, they were unsuccessful in 1995 and men like Nirmaladevan merely went to their villages around Jaffna and returned in six months. Is Nirmaladevan really busy or is it that he hates talking of his experiences during the civil war?

Samanth has an almost similar experience with Chelliah Thurairaja, a retired Major General in the Sri Lankan army. Thurairaja continues to work even after retirement, just as he continues to play golf with his fellow army officers. What makes him tick? Samanth wonders. How did he survive the Sri Lankan government’s “Sinhala Only, Tamil Also” policy which made it mandatory for serving civil servants and soldiers to learn Sinhala to get further promotions? Samanth has better luck with Thurairaja (than with Nirmaladevan), who opens up a bit, though he is very guarded in what he says. Not learning Sinhala was a way of penalizing onself, Thurairaja had reasoned to himself. If in France, one would learn French just as one would learn German in Germany. Samanth never fully figures out how in his own country, Thurairaja was able to put himself in the shoes of a foreigner who opts to learn the most widely spoken tongue in order to get by. Thurairaja does put him on to Sivagnanam, another army officer who used to be a radiographer in the army and had migrated to Canada, someone who could possibly speak more freely. Samanth goes to Toronto, but never get to meet Sivagnanam. However, he does talk to Ravi Paramanathan, a retired army major, who never supported the Tigers or even the idea of Eelam, but feels betrayed by the Sri Lankan government’s treatment of Tamils.

In his quest to tell his readers about the events which led to the demand for Eelam, the creation of the LTTE, its defeat at the hands of a marauding Sri Lankan army and the continued victimization of Sri Lanka’s Tamil community, Samanth does not restrict himself to Sri Lankan Tamils who served in the Sri Lankan army. Over a few years starting from just after the Sri Lankan army killed Prabhakaran on the banks of Mullivaikal, Samanth made a number of trips to Sri Lanka, each trip lasting over many weeks, travelled all over the island and met all sorts of people ranging from Tamils who continue to long for the LTTE and the possibility of Prabhakaran returning to lead the struggle once again, Hindu Tamils who work for and promote the Hindu Swayamsevak Sangh, Sinhala Buddhist leaders such as the liberal, left-wing Samitha who thinks that the Tamils of Sri Lanka have honest grievances, the chauvinist, right-wing Omalpe Sobitha, Sri Lankan Muslims, journalists, bloggers, Sinhalese soldiers, Sinhalese politicians, LTTE war widows etc.

If I have given you the impression that Penn State/Columbia educated Samanth Subramanian toured the island with machine like efficiency, working non-stop, pestering people to part with their secrets, please forgive me. No, during his Sri Lankan sojourns, Samanth seems to have spent a fair of time drinking beer, arrack, whiskey or whatnot and talking shop with like-minded liberal journalists and falling seriously ill at least once. However, from Samanth’s rambling travels and meetings comes out a very incisive and coherent discourse on Sri Lanka’s past and the current state of affairs in the emerald paradise. Most importantly This Divided Island is unbiased, despite Samanth obvious sympathy for Tamil grievances and their current state of utter despair. All of this in very elegant prose, which is also simple and easy to read.

Samanth is a reporter and he keeps his analysis and opinions to a minimum even when detailing the most horrible atrocity or violation. I had known that the Tamil civilians who were herded together into a small strip of land at Puthukkudiyiruppu during the Tigers’ death throes had a horrible time as the Sri Lankan army shelled and rocketed them without regard for human life, in a desperate bid to crush the Tigers. However, Samanth’s detailing of those days, final days for many thousands of human pawns, left me breathless with shock and anger. Granted that many of those civilians were Tiger sympathizers and even relatives, what right did the Sri Lankan army have to shell no-fire zones, including hospitals, with such wanton frequency, which can only be interpreted to denote an intention to kill as many as possible, without any consideration of age or gender or non-combatant status? However, it was not only the Sri Lankan army which resorted to such inhuman behavior. In those last days, the LTTE which had never been shy of forcible conscription, went out of its way to snatch young boys and girls from families, forcing them to take part in a fight in which death was almost certain. Families pleaded in tears as their teenagers were taken away, never to return. As Samanth details how the Tigers used Tamil civilians as human shields, one scene from those final days at Puthukkudiyiruppu sticks in my mind. A man in his fifties tells a young Tiger in a calm voice that they ought to let the people go at least then. The Tiger whips out a pistol and shoots the man dead.

Samanth tells us that the LTTE had always been cruel, right from its inception. Even when the LTTE numbered just around 400 men, they were all yes men, as spies reported on spies and dissent was stamped out. Apparently Prabhakaran often asked new joiners if they would be willing to kill a brother who joined a rival Tamil outfit.

Many Sinhalese have a genuine fear of an “Ekanta Demala Rajya”, a Greater Tamil Nation stretching from Tamil Nadu to Malaysia. The Sri Lankan government has played on this fear and used it to suppress the Tamil community. The Mahavamsa, a purported history of the Sinhalese race since their arrival in Sri Lanka from Bengal and the growth of Buddhism in the Island, celebrates the story of Dutugemunu, a prince who fought Elara, a Chola king who invaded Sri Lanka. Mahavamsa says that Elara was actually a fair King who did not oppress Buddhism, but despite that Dutugemunu battled Elara’s forces for 13 years and finally killed him. Thousands of Tamils were massacred. Later when Dutugemunu suffered from the pangs of conscience, Buddhist monks comforted him by saying that the “Tamils were heretical and evil and died as though they were animals.” Both the Mahavamsa and Dutugemunu are celebrated in Sri Lanka and a famous Sri Lankan army regiment, the Gemunu Watch, is named after King Dutugemunu, not exactly actions which would inspire the Tamil minority to show confidence in the government and the majority community.

Respected Sri Lankan journalist Lasantha Wickrematunge who often spoke out against the government’s human rights violations was shot dead by government-backed assassins a few months before the civil war was over. After the Sri Lankan government won the war, its actions akin to doctors excoriating a tumor, destroying the last suspicious cell with heavy chemotherapy, the harsh treatment of minorities has continued. With the Tamils totally crushed, organizations like the Bodu Bala Sena have started to target Tamil speaking Muslims, at times destroying their places of worship.

Why is it that Sri Lanka’s Tamil speaking Muslim community has never identified itself with Sri Lanka’s Hindu and Christian Tamils? Samanth tells us that the LTTE had, throughout the 1980s, made attempts to recruit from Sri Lankan Muslims, but it came to nought and later in October 1990 the LTTE ruthlessly expelled around 24,000 Muslims from Jaffna, forcing them to be refugees in their own land. If Sri Lanka’s Hindu and Christian Tamils can unify on the basis of their mother tongue, why can’t Sri Lanka’s Muslims do the same? There seems to have been no history of Muslims placing their Tamil identity over their religion, though almost all Sri Lankan Muslims are Tamil speakers. I wish Samanth had addressed this issue.

“Sarath Fonseka” is another topic I wish Samanth had bothered to tell stories about. Why and how did the hero of Sri Lanka’s victory become estranged from the Rajapaksa brothers and end up in jail? There is a stray reference to Fonseka’s portraits in a Buddhist viharaya built next to a Tamil Hindu temple on Katys, and their subsequent replacement with Rajapaksa’s and that’s all that there is on the former army chief who, after the victory, aspired for political power.

On the whole, This Divided Island is an excellent book, a must-read for anyone interested in knowing more about Sri Lanka.

Tuesday 15 July 2014

Book Review: Lamplight - Paranormal Stories from the Hinterlands, by Kankana Basu

There are ghost stories and ghost stories, some fall flat and some make you sit up in fright, hair on end, desperately reaching out for something to hold on to. I think the best ghost novel I have read is Little Stranger by Sarah Waters which was shortlisted for the Booker Prize in 2009. I have read Kankana Basu before and when I found out that her latest offering was a collection of ghost stories, I was, to put it mildly, shocked. Both of Basu’s previous offerings, Vinegar Sunday and Cappuccino Dusk, are set in Mumbai and revolve around large Bengali families, their retainers and friends. Even though both these books tackle a number of contemporary issues, there is a definitive feel-good factor about both these books which I was sure would be missing in a collection of ghost stories. I couldn’t have been more wrong.

Lamplight consists of eight short stories, all of which, except one, are set in Monghyr, Bihar, in pre-Independence India and revolve around a large extended Bengali clan, their neighbours and servants. The Chattopadhyays are rich and aristocratic, but also friendly and warm. The matriarch of the family has three sons, Srikanth, the eldest, a doctor, affectionately referred to as Boro Jetha, Deep the second son and Balai, the youngest, a novelist. The grandsons outnumber the granddaughters and all the grandchildren evolve and grow as the stories progress. Srikanth has two sons, Tutul who is shown to have become a lawyer as we reach the end of the collection and Nabendu (Benu) who throws off a debilitating ailment and becomes an industrialist, Deep has two daughters Mala and Mini and Balai has three sons, Sutanu (Shontu) and Ronojoy (Ronny) and Manohar (Montu). Balai’s spouse Bonalata has a crucial role in one of the witch-hunts. There is no shortage of friends and neighbours either. Balai’s friend Nirmal Choudhury plays a pivotal part in Séance, the first story in this collection and for me, the best of the lot. Kumkum, the maid and Raghu Kaka the gardener are flesh and blood characters who make their mark despite their lowly stature.

I found all members of the Chattopadhyay clan, their friends and hired help to be lovable, except for maybe Deep in The Séance. The feel-good factor, which I think is Basu’s hallmark, is ever present as we are gradually introduced to various characters. The ghosts dutifully make their appearance in every story and I didn’t particularly find them to be scary, and to be honest. I don’t think they were meant to be. These are stories which a twelve year old could read and not have nightmares. Basu’s ghosts are gentle and sometimes helpful, as in the Terrace, where they help football genius Ronojoy get a job with a manufacturing concern in Bombay.

Basu is extremely good at conveying the atmosphere of 1930s India, without appearing to try very hard. There is no reference to the independence movement or poverty, but there is no doubt that we are in pre-independence India. Basu’s characters are very individualistic and different from each other. For example when describing Chitra pishi, a neighbour, we are told that she of average height, had a stick-like physique, was pigeon chested, sallow skinned and gaunt of countenance. However, she had a fine pair of eyes which nullified every shortcoming in her appearance.

In The Guide, Shontu is dying to ride Montu’s new, red bike and when a need arises for someone to reach faraway Sitamarhi and deliver medicines to Dwarakanath Misra’s daughter. Shontu promptly volunteers and I wondered for a while if I was reading the Adventures of Tom Sawyer rather than an Indian collection of ghost stories. However, a ghost eventually made an appearance, followed by a number of rustic Indian characters and my confusion faded away.

One of the stories, Monghyr Fort, revolves around an actual fort and when I googled the name, I realised that Monghyr Fort actually exists. In this story, Basu’s references to the Slave Dynasty and characters like Mir Kasim seem to be authentic.

In Blood Emerald, the final story in the collection, Basu moves away from Monghry and takes her heroine, one Avantika, to faraway Mahabaleshwar where she meets the ghost of a pretty Maharashtrian lady who died in unhappy circumstances. Despite the change of venue, the same old world charm, courtesy and grace of a bye-gone era are kept alive.

On the whole, Lamplight left a very pleasant aftertaste in me, it’s the sort of story you could read after a tough day at work. I recommend this book to all those who are interested in ghost stories and all others who, like me, like to read good stories.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

.jpg)