Tuesday, 8 December 2015

Short Story: A Tale Of Two Speeches

My mom gave me an encouraging smile as I wriggled my leg under the table. I wasn’t nervous, not in the least. Rather, I felt infinitely superior to the lesser beings who were all around me, some of whom awaited us in the college auditorium. I’ll keep it simple,’ I told my mom who didn’t look too pleased at my proposal to dumb down.

‘You do what you think is right,’ Sheela auntie told me. Sheela auntie was my mom’s best friend. She didn’t need to give any such instructions to her son Arun who looked very comfortable in his skin, finishing off the last of his sweet nectar-like coffee with a loud slurp.

‘Some more coffee for you Arun?’ my mom asked.

‘Yes, please Kala auntie. This is lovely coffee. One of the things I miss over there. The coffee one gets there is atrocious. Like a bitter pill.’

‘I’ve got used to it,’ I said. My mom gave me a pained look as she rang the bell.

The attendant who came in beamed at all of us.

‘Krishna, one more coffee for Arun.’ Krishna was in his early fifties and I’ve known him since I was a toddler, just as I’ve known Sheela auntie and Arun since my infancy.

‘What about you moné?’ Krishna asked me even as he nodded in response to my mom’s order. Mon literally meant ‘son’, but in Kerala, it was liberally used by all and sundry when addressing a much younger man.

‘No, not for me.

‘When do you leave?’ Krishna asked me, as he started to walk out.

‘In a week’s time.’

‘And you moné? Krishna stopped at the door, his hand on the doorknob.

‘I’ve just got here. I’m not going back,’ Arun said with a chuckle.

‘I wish,’ Sheela auntie said. ‘He’ll leave in two weeks,’ she told Krishna.

‘Get him married before he goes away,’ Krishna advised her and left.

‘If only these kids would obey us in matters such as these,’ my mom started one of her usual tirades.

‘Oh never mind them. I’ve got used to the idea that Arun may not marry the sort of girl I have in mind. It doesn’t matter. I’m good at adjusting, even when I don’t get what I want.’

‘Oh Arun is a sensible boy. Unlike Shibin. Shibin just doesn’t care how I feel.’

‘But Shibin will make you happy. You always get what you want.’ Sheela auntie’s voice had become mellow. A little too mellow. It wasn’t too long ago that my mom had pipped her to the principal’s post, a position both women had aspired to, ever since they joined St. Theresa’s as junior lecturers.

Krishna came back with a cup of coffee for Arun and lingered.

‘What’s it Krishna?’ My mom’s voice was sharp. We were in the principal’s office and she reigned supreme in there.

‘Oh nothing!’ Krishna left in a huff. Arun chuckled.

‘He wants to talk to me regarding his son. He’s been pestering me to find a job for him in America.’

‘As if you are working in the Gulf! ‘You can’t take all and sundry to America!’ Sheela auntie was annoyed.

‘He knows that,’ my mom said. ‘He’s not that stupid.’

‘It’s okay Mummy,’ Arun told Kala auntie. ‘I’ll speak to him anyways. I do have a friend in Qatar who may be able to’

‘That would be wonderful,’ both women chimed in.

I looked at my watch and said, ‘didn’t we say 11:00 a.m.?’

The four of us trooped out, walking through long corridors, past classrooms, some noisy and some suspiciously silent. ‘B.Com, first and third years. M.Com, both years,’ my mom whispered to me, as I followed her. Sheela auntie and Arun brought up the rear.

‘You have nothing to do with any of them right? Even when you used to teach?’

‘Nope, why would a physics teacher have dealings with commerce students?’ I gave mom a knowing smile, even though I no longer shared her contempt for students who studied subjects other then science, engineering or medicine.

‘Sheela would know them somewhat. She takes English for First Year B.Com.’ Mom spoke loud enough for Sheela auntie to hear.

‘I must have taught all of them, but I am so bad with names, I doubt if I can recall more than a few names.’

‘But what about your current class? Surely you would know their names?’ Arun was bemused.

‘The English literature department has eight teachers. We take turns to teach B.Com students. I devote most of my time for the M.A students, especially the final years.’ I realized that contempt for other disciplines was not the monopoly of science teachers.

‘Arun, if you want an introduction, why not say so? Your mother would not mind introducing you to any number of pretty young women.’

‘Ha! Ha! Very funny.’

There was no time to say more since we were suddenly inside the auditorium, which was half full. There must have been around two hundred students in there, in ages ranging from the late teens to the early twenties. I was suddenly conscious of being a single man, albeit in my early thirties. I turned around to look at Arun who showed no signs of nervousness, let alone look flustered as I was.

The Head of the Commerce Department walked over to us, followed by three colleagues. Gracy auntie was also an acquaintance, but I didn’t know her as well as I knew Sheela auntie. I was sure that Arun didn’t know her all that well either, Gracy auntie was around five years younger than our mothers and they weren’t close, but Arun greeted her like a long-long friend, as he did with her colleagues who were even younger. One of them actually blushed. It helped that Arun was a few inches taller than the average Malayalee and rather good-looking.

‘This is such an honour. Two boys from our town, children of our own faculty, both did MBAs from the US and now both of them are successful investment bankers in New York.’

‘I’m not an investment banker. I do econometrics modeling for a fund. And I did an M.S in Finance, not an MBA.’

Gracy auntie gave me a knowing smile, but I was sure she didn’t have a clue about the difference between investment banking, which Arun did, and econometrics modeling for hedge funds.

We walked over to the podium and took our seats. Gracy auntie started to speak and I tried to focus, but failed. Both Arun and I were expected to speak about what we did in the US, sort of a how-we-did-it, as in, how did each of us make it out of Kerala and do our Masters in the US and find employment in a supposedly lucrative field. Unlike Arun who did bread and butter investment banking, what I did was highly specialized. Econometrics involved the use of mathematical tools and models to price call and put options and to assess volatility in the market. My main role was to prepare models to price and value the derivatives the hedge fund I worked for invested in. I was currently working on a more efficient framework for pricing options using time integration schemes and nonlinear financial integration modeling, but I was sure that the audience would not appreciate any of that. I had to keep it simple and relevant. I realize that my mom was prodding me with her feet, none too gently. Grace auntie had finished her introduction and another teacher, I think her name was Vimala, was speaking, rather reading from a prepared sheet.

‘Shibin did his chemical engineering from BITS Pilani and then went to Texas for his Masters in Finance.’ Now he works for’

I frowned. I distinctly remembered writing in the bio I had prepared the previous night that I went to Austin for my Masters. University of Texas, Austin, that’s what I had written. What was the harm in saying so? Did Vimala know a lot about the US to modify what I was painstakingly written out for her benefit?

‘Arun did his mechanical engineering from NIT Warrangal and worked in Jamshedpur for two years before doing an MBA from Duke in Carolina. Duke in Carolina! Just like that. I was surely Arun had written Duke University, Fuqua School of Business, Durham, North Carolina. Was Vimala too scared to pronounce ‘Fuqua’? I turned sideways to look at Arun who seemed to be having a small laugh at the faux pas. ‘Now he works for XYZ, a top investment bank in New York.

Soon the introductions were over and I was facing the multitude. I took a deep breath as I started to speak. I knew I would end up speaking first, since my mom was the principal. If Sheela auntie had pipped my mom in the race to for the top job, I would be waiting for my turn, as Arun was. Arun didn’t seem to mind.

‘I use econometrics to build financial models for a hedge fund. How many of you know what a hedge fund is?’ I asked the students and waited for a response. There was none.

‘I’m sure you know what a mutual fund is.’ There were a few nods. ‘A hedge fund is a fund, in that it pools money from a number of people and makes investments, like a mutual fund. However, unlike mutual funds, a hedge fund collects money from a limited number of sophisticated individual or institutional investors, in other words, knowledgeable investors who can also afford to place their money at risk and invests them in a diverse pool of assets, using contrarian tactics, often with complex portfolio construction.’

I looked at the students again. Most of what I said had clearly gone above their heads. One would expect students studying commerce to know what a hedge fund was, but this was small town India where the smartest and the best joined either engineering or medical colleges.

‘Let’s focus on the basics,’ I said. ‘What’s a fund? Silence. ‘A pool of money.’ Why do people pool their money? Why is a fund managed by a professional fund manager? Why is a fund regulated by a regulator? In India, we have SEBI. In the US, a fund would be regulated by the SEC and FINRA.’ I continued to ask simple questions and give answers. After a while, I started to receive some responses and though they were rather silly, I felt encouraged. I continued in that vein for half and hour and concluded by saying that though I hadn’t spoken about what I did for a living, I hoped that I had added to their knowledge about investment management in general and funds in particular. There was some muted applause and I sat down feeling satisfied. My mom beamed at me. Sheela auntie gave me a congratulatory nod of her head. Arun however avoided my eyes.

‘I am an investment banker and I do leveraged buy-outs at XYZ ,’ Arun announced. I waited for Arun to explain what a leveraged buy-out was, something rather straightforward, but he didn’t. Instead, he spent ten minutes taking about XYZ, the i-bank he worked for, how it had a pedigree of over 100 years and how it had offices all over the world and its bankers led a jet-setting lifestyle. Then he went back to talking about leveraged buy-outs, using a lot of technical jargon, which sounded quite complicated, but actually wasn’t.

Arun mentioned a few anecdotes about his clients and their top honchos, taking care to disguise their names and identity. He then went back to talking about leveraged buyouts and the hostile takeovers which usually followed such a buyout. Soon, Arun had his audience at the edge of their seats even though they did not understand most of what he was saying. He gave a recent example of a leveraged buy-out, one which had hogged headlines in the financial press, but was actually handled by another investment bank, but who cared? The audience behaved as if Arun was a rock star or as if they were watching the latest Hollywood thriller. In vain I waited for Arun to say that a leveraged buyout was merely the acquisition by one company of another using a whale lot of borrowed money, at times even pledging the assets of the target company. If only Arun would give that basic clarification, most of what he said would make sense. Just another form of M&A, I wanted to stand up and say, only to make things easier for the young ones listening to Arun.

I turned to look at Sheela auntie and my mom. Sheela auntie was beaming, this time genuinely, though I was sure she didn’t understand any of the jargon Arun used. My mom was also listening intently, though at times she turned her head this way and that, to scan the students. I knew that she wasn’t too happy even though she hid her feelings well.

Arun spoke for almost an hour. Towards the end he concluded by saying that he hoped to see a number of St. Theresa’s students working as investment bankers in New York, London and other parts of the world. If they studied well and showed single-minded determination, they could easily reach where he had got to. The audience was ecstatic and gave him a standing ovation.

As well left the auditorium, Sheela auntie and Arun were all smiles. I too smiled at them and congratulated Arun for his excellent speech. I decided to look at the whole thing philosophically. After all, Arun’s victory had little value, but my mom didn’t say a word to me for the rest of that day.

Tuesday, 1 December 2015

Book Review: Magic in the Mountain, by Nimi Kurian

It’s a long while since I read a book essentially meant for children. A children’s book need not be about children, but Magic in the Mountain is, which would normally make it all the more unsuitable for an adult. Nevertheless, since I’ve followed Nimi Kurian’s writings in the Hindu for a while now, when I heard that her first novel has been published, I couldn’t resist buying Magic in the Mountain’s kindle edition, even though, as I just said, it is not really meant for those above the age of fourteen.

Nimi takes us to Coonoor, a little hill town nestled in the Nilgiri mountains. We meet two young kids, Priya and Pradeep, in tragic circumstances – their parents have been killed in a road accident. Aunt Sheila, their mother’s sister, is kindness personified and whisks the kids off to Coonoor where she lives. Coonoor is a magical place on its own but when Priya and Pradeep meet special characters such as Kitty the kitten and Sanjana Banerjee who is forever knitting, it takes on a special aura.

Magic in the Mountain reminded me of Enid Blyton’s Famous Five until Nikhil put in an appearance and then I was reminded of Blyton’s Barney Series. The two kids go exploring on bikes and because Nikhil doesn’t have one, he helps himself to Mr. Swaminathan’s bicyle without his permission. I’ll not disclose any more here, rather, I’ll will leave it to you to read this book for yourself and find out.

Nimi’s Coonoor has remnants of the 70s – it has Imperial Stores and Babu Tailors. However, environmental degradation has done much damage to the hills and Priya and Pradeep can only look on helplessly. Into this setting arrives a big, bad mystery, personified by Mrs. Manju Sinha, aka Madam Ladida, who knows a bit of magic and has two assistants in the form of a red blanket which can fly and a snake which doubles up as a butler. Alok, the evil Scientist, called Upset by his former classmates, is Madam Ladida’s main ally, until things change towards the end.

The kids land up in all sorts of troubles and their poor aunt is also dragged in. However, they have some sensible allies such as Professor Varadhachari, Subbiah, the park superintendent and Mr. Swamination, the proprietor of Imperial Stores. I do not want to say any more and give away the plot, save that it revolves around damage to the environment, a subject which is of interest to everyone in these days of climate change and its devastating consequences.

Nimi’s language is limpid as the tale unwinds with decent speed. I’m sure kids will love Magic in the Mountain and many an adult too!

Wednesday, 21 October 2015

Book Review: Three by Krishna Udayasankar

Having reviewed Krishna Udayasankar’s Aryavarta Chronicles, a trilogy based on the Mahabharata, I was very keen to read Three, Udayasankar’s latest literary offering. I was not disappointed.

Three is loosely based on the founding legend of Singapore and Udayasankar’s imagination conjures up a host of interesting characters set in the early thirteenth century, a time when the Chinese Song Dynasty’s influence in the South China Sea was at its zenith. The protagonist, Sang Nila Utama, is a complex person, a man who is honest and good, but does not want to be King, despite the royal blood flowing in his veins. Utama’s father, Prabhu Dharmasena, the sailor king of Srivijaya has a string of bad luck, which culminates in his losing Palembang, his final seat of power, to the Cinas, this despite having married off one daughter to the Emperor of Cina and another to the Ambassador from Cina. Taking to the seas with his elder son Mutthaiah, Sang Nila Utama and others, Dharmasena seeks refuge and alliances.

Nila grows up to be a hardy young man, brave, honest and skilled in warfare and fighting pirates. Mutthaiah and Nila are initially close, but soon they drift apart. Mutthaiah was born to be king and does not hesitate to grab power when opportunity strikes. Nila on the other hand does everything possible to avoid power and responsibility. Despite Nila’s determination to evade royal duties, he ends up marrying Sri Vani, a marriage which would have been termed opportunistic if the couple weren’t madly in love.

Finally, fate takes Nila to Tumasik, a land said to be inhabited by pirates. Instead of clearing the land of so-called pirates, Nila takes on an onerous responsibility, one which will shape the destiny of that region. I am not going to divulge any more here. Please read this excellent book to find out for yourselves.

Having read and reviewed Udayasankar’s Aryavarta Chronicles, I’ve come to expect strong female characters in each of Udayasankar’s books. Three is no exception though I had to wait a fair amount until, towards the middle of this slim volume, I was introduced to Sri Vani. Beautiful, proud and loyal, Sri Vani embodies all that can be good and honest in a royal personage of those times and forms a perfect counterfoil to Nila’s rough and ready character.

Udayasankar tells us that Prabhu Dharmasena had Chola blood in his veins, not surprising since the Cholas had in the 11th century invaded Srivijaya. Names such as Mutthaiah add flavour to the Chola heritage. However, I waited in vain for Udayasankar to describe how Prabhu Dharmasena, Mutthaiah, Nila and others in the royal family looked. Were they more Tamil than Indonesian in appearance? Were they as fair-skinned as modern-day Malays? I also wish Udayasankar had spent some space and time to describe the sort of food her characters ate. Did they eat Dravidian Pittu or did they eat noodles? Were they vegetarians? I doubt it, especially because Nila goes hunting once, but is there any rule against vegetarians going on a hunt? And finally what language did they speak? There is a stray reference to Nila’s ability to curse in five different languages, but did Nila and his family speak any Tamil at all? Of course, these are minor quibbles and Three is an excellent read, especially because Udayasankar's prose is lyrical and beautiful.

Monday, 19 October 2015

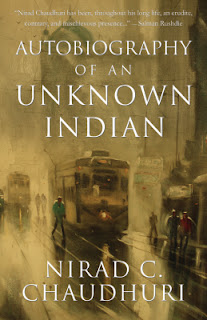

Book Review: Autobiography of an Unknown Indian, by Nirad C. Chaudhuri

Nirad C. Chaudhuri’s Autobiography of an Unknown Indian, which came out in the early 1950s, has been on my reading list for over a decade, but because Chaudhuri was literally, for me, an unknown Indian, I was able to put it away for so long, despite its reputation as a literary heavyweight. Why would an unknown Indian want to write his autobiography, I wondered? And what would he have to say?

Modesty from a Non-Native English Speaker

Chaudhuri is quite modest as he sets sail. He announces very early on that he has no illusions about his mastery over the English language. ‘An author whose English was not learnt from Englishmen or in any English speaking country’, he describes himself, though it is clear that his writing does not have any reason to be shy. By the time Chaudhuri adds a bit later that he has never lived outside India, I am convinced that I am reading a master of the English language, possibly the best Indian English writing I’ve ever read, better than even Vikram Seth’s. Since Chaudhuri was around 50 when he published Autobiography of an Unknown Indian, the only other conclusion I can draw is that Chaudhuri did not come from a privileged background, something borne out from his disclosures in the rest of the book.

Brutally Candid

If you are a successful sports star or a politician or a businessman, writing an autobiography should be a straight forward, how-did-I-achieve-success narrative. Writers on the other hand, maybe because success as a writer is as much a function of the writer’s mental makeup and past trauma as it a result of hard work and persistence, make a virtue of excoriating themselves in public. JM Coetzee’s auto-biographical novel Summertime: Scenes from Provincial Life comes to mind. V. S. Naipaul arranged for sufficient personal detail to be provided to his official biographer Patrick French to write some pretty interesting stuff. If JM Coetzee strips himself bare and shines an unflattering light on his naked body in Summertime, Chaudhuri does the same for his community and country, without dissociating himself from either.

Family

Chaudhuri starts off by giving a detailed description of his parents and other family members. We are told that his father was a successful lawyer and the Vice-Chairman of the Kishorganj municipality. Those days, there were two categories of lawyers, Ukils with higher academic and professional qualifications and Muktears who largely handled criminal cases. Chaudhuri’s father was Muktear who made enough money to buy unlimited quantities of books for his children, who unusually for his time (and even by modern day standards) thought that education was an end by itself. The Chaudhuri children evidently grew up in a literary environment. One can’t help but be impressed when Chaudhuri says that he cannot remember the time when he did not know the names of Queen Victoria, Prince Albert, Napoleon, Shakespeare and Raphael. I think I heard of Raphael when I was 21! ‘The next series comprising Milton, Burke, Warren Hastings, Wellington, King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra is almost as nebulous in origin. Lord Roberts, Lord Kitchener, General Buller, Lord Methuen, Botha and Cronje, entered early thanks to the Boer war. Next in order came Mr. Gladstone, Lord Rosebery, Martin Luther, Julius Caesar and Osman Pasha (the defender of Plevna in the Russo-Turkish War of 1877-78) – these too belonging to the proto-memoric age. The beginnings of true memory in my case were marked by the names of Fox and Pitt, and Mirabeau, Robespierre, Danton, Marat, Junot (Napoleon’s marshal) and also perhaps Georve Washington. On the literary side, in addition to the names of Shakespeare and Milton which we imbibed unconsciously, we came to know of Homer as soon as we began to read the Ramayana and Mahabharata, which was fairly easy.’

When the family moved to Kolkata, Chaudhuri found school life to be a disappointment. However, the wider literary life in Calcutta was more lively and generous.

Rooted to the Bangla Soil

Even as he taught them English, Chaudhuri’s father made sure his children did not neglect Bangla literature. Chaudhuri takes us on a tour of the Bengali literary world, introducing us to its litterateurs of his time in the process. He starts with Michael Madhusudan Dutt, a wealthy Bengali who converted to Christianity. Chaudhuri calls him the greatest exponent and greatest martyr of Bengali humanism and a great scholar. We meet Bankim Chandra Chatterji who was, according to Chaudhuri, positively and fiercely anti-Muslim, the creator of Hindu nationalism. These men were not, in their days, darlings of the masses. We are told that Rammohun Roy and Tagore were underrated, ridiculed, slandered and even persecuted in a manner wholly undeserved and unexpected. Even a Hindu conservative like Bankim Chandra Chatterji was not fully understood by the masses. Vivekananda became a hero only after the Parliament of Religions at Chicago gave him an unexpectedly favourable reception. Most funnily, I learnt that Tagore's Bangla was not considered to be chaste or classy enough by many and this perception did not change until he won the Nobel!

Chaudhuri talks of Brahmo Samaj as an organisation whose morality was derived from puritan Christianity. It led a moral crusade attacking four vices namely sensuality, drunkenness, dishonesty and falsehood. Chaudhuri tells us that none of these vices had reached diabolic proportions, since feebleness and passivity permeated even the vices. Chaudhuri was evidently not a follower of the Brahmo Samaj.

On Calcutta and Bengalis

Even in those days, Calcutta was not a very clean city. Apparently Bengalis washed themselves and their clothes more than was necessary and tonnes of washing was always hung out to dry and garbage was dumped on roads. To slip on a mango or banana skin and have a sprained ankle was a very common mishap in Calcutta, we are told.

Elysium Row was a dreaded street since it had, Number Fourteen, the Headquarters of the special police or the political police. Apparently there were few Bengali young men with any stuff in them who did not have dossiers in Number Fourteen, and many had to go there in person to be questioned or tortured, or to be sent off to a detention camp.

Bengalis were very superstitious. For example, men tied up their hair in a knot before going to a WC since WCs were believed to be the favourite haunts of evil spirits who would possess them unless their hair was tied up. Cow dung was sprinkled liberally to purify things. Elderly women sometimes went nude when working in the kitchen since their clothes would otherwise be contaminated by food. The common man was opposed to all sorts of reform or to the emancipation of women. The sternest denouncers of Rammohun Roy or Tagore were the gentry of Calcutta.

Mixed Feelings Towards The British

Though Chaudhuri is supposed to be an anglophile, his feelings towards the British, which he conflates with that of Indians in general, are definitely mixed. According to Chaudhuri, during the Boer War, one-half of India automatically shared in the English triumph, while the other and the patriotic half wanted the enemies of England to win. Indians gloated over allied reverses and glory in German victories in both World Wars. This was done less openly in 1914 than in 1939.

Once when attending a concert in Calcutta with an English friend, sitting in the gallery, Chaudhuri saw row upon row of Englishmen and Englishwomen in graceful evening dress below him and there were no Indians. The thought of dropping a bomb on the crowd below came to Chaudhuri in his heated and excited state.

As a student, Chaudhuri too defaced pictures of Moghul emperors and English governor Generals. Even when they wrote of the Black Hole as a tragedy and the battle of Chillianwallah as a draw, in exam papers, they were convinced all the while that the former was a myth and the second a defeat for the English.

Once Chaudhuri and his brothers visited a battleship which had come to Kolkata. He was disgusted by the way Indian crowds behaved and Indian constables (under English sergeants) treated them. The crowds followed no queue or rules and swarmed all over. The police used batons, lathis and whips freely on the crowds. Apparently, that spectacle repeated was year after year on the visit of ships of the East Indies Squadron. Chaudhuri tells us that the ‘display of racial discrimination not surpassed in all the squalid history of Indo-British personal relations. The arrogance and absence of consideration shown by one side was matched only by the indiscipline and lack of self-respect shown by the other.’

Outright or fulsome praise for the British Empire is entirely missing in Autobiography of an Unknown Indian. One gets the feeling that Chaudhuri not only admired the British Empire and its achievements, he also envied them in the position of one colonised. Where there is praise, it is faint and even disguised. For example, when discussing the education system devised for India by the British, he says that ‘the educational system of British India has been accused of being only a machine for turning out clerks and officials. That certainly is true if we test the system by the use which was made of it in average instances and judge it by its average product. But it is not true if we take into account the intention of those who created the system. Many passed through the British Indian educational system mechanically, their approach akin to that of a man with a gun who uses it as a cudgel.’

Chaudhuri had no contact with English social life in Calcutta. Those were days of racial privileges and certain parts of Eden Gardens were roped off. Chaudhuri never went close to the English for he did not wish to invite rebuffs, he tells us.

Attitude Towards Muslims

Chaudhuri tells us that they learnt nothing of Islamic culture, although it was the spiritual and intellectual heritage of nearly half the population of Bengal and living in East Bengal, they came into intimate and daily contact with Muslims. Creators of modern Indian culture in the 19th century completely ignored the Muslims. After the end of Muslim rule, Hindu society had completely broken with Islam. ‘There was retrospective hostility towards Muslims for their one-time domination of the us. Even before we could read, we had been told that the Muslims had once ruled and oppressed us, that they had spread their religion in India, with the Koran in one hand and the sword in the other, that the Muslim rulers had abducted our women, destroyed our temples, polluted our sacred places. In nineteenth century Bengali literature, the Muslims were always referred to under the contemptuous epithet of Yavana.’

Despite doing his best to be neutral towards Muslims and Islam, Chaudhuri mentions an incident from school when Muslim students protested against acting certain scenes from a Bengali drama for the school anniversary day. Whilst admitting that the scenes were indeed offensive towards Muslims, Chaudhuri says that he went home in tears.

Chaudhuri’s views towards Muslims were influenced by his uncle Anukul who was in turn influenced by Bepin Chandra Pal. Ankul took the view that Pan Islamism was the greatest danger facing Indian nationalism. Chaudhuri agrees and for this reason, during the Turco Italian War and the two Balkan Wars when most Indians pro-Turkey, Chaudhuri was anti-Turkey.

On India’s Defeat By Islamic Invaders

Chaudhuri delves into the Hindu psyche in detail as he seeks to understand how Muslim rulers managed to conquer India and control the majority Hindus for so long. Chaudhuri says that Muslim rulers, as long as they remained strong, had no Hindu rebellion to fear. Provided they paid a commensurate reward they could count on being able to enlist any number of Hindus to act as administrators, army commanders, suppliers and advisors. Hindus would even advise them of the best means of bring other Hindus under subjugation. However, Hindu homes and kitchens were out of bounds for Muslims even as Hindu society tightened rules against intermarriage and commensality during the period of Muslim rule. Chaudhuri quotes Sarat Chandra Chatterji who summed by the underlying principle of Hindu behaviour with the example of a woman who has a low caste paramour and who boasts that although she has lived with him for twenty years, she had not, for a single day, allowed him to enter her kitchen.

According to Chaudhuri, India was a colonial empire of Islam. Unlike Persia which was conquered by Islam during its formative years, India was conquered after the Islamic order was fully grown and fully self-conscious. Chaudhuri refutes the argument that Islam declined in India because of Aurangazib’s (sic) intolerance. There were other Muslim monarchs who were less tolerant of Hinduism. ‘An Islamic society stretching from the Atlantic to the Oxus was not founded on the basis of perfect equality between the conqueror and the unconverted conquered. If an empire is founded as well as destroyed by intolerance, the intolerance ceases to have any causal significance for any part of the process. Tolerance or no tolerance, Indian Hindus were never reconciled to Muslim rule. The empire ceased to receive new administrators and soldiers from Iran and Turkestan and the resident Muslims were too denigrate.’ In short, the decline of the Moghul Empire was not due to uprisings by the Marathas or the Rajputs. Globally Islam had declined and this decline took India in its stride. ‘The revolt of the internal proletariat against Muslim rule was only the ass’s kicking of the sick lion.’

Weaknesses of Hinduism

Chaudhuri ticks off various Hindu weaknesses one by one, even as he does not even try to disassociate himself from his community. He gives the example of a contractor whose cow was strangled accidentally. The contractor was forced to wear sackcloth, drink half a glass of bovine urine and fast for a day. For the next three days, he lived and slept in the open on the spot where the cow had died and also abstained from eating anything but plain rice without even salt. He had to beg for alms, bellowing like an ox. Later he was sprinkled with cow urine even as all Brahmins of the locality were fed and the priests amply rewarded.

Chaudhuri says that the ethical immaturity of Hindu society is apparent from its failure to develop a sense of personal moral responsibility. ‘Taking of bribes, not giving value for money in public services is sanctioned or condoned by habit or custom. The doctrine of karma has dulled the Hindu’s conscience by entrusting the ship of morality to a sort of gyropilot,’ Chaudhuri says.As for Hindus who boast of the greatness of their heritage without much knowledge, Chaudhuri has only contempt. We are told that many Hindus from Punjab spoke of the greatness of Hindu culture and religion without being able to read not only Sanskrit but even Hindi. Colleagues who chided Chaudhuri for his fondness for English and French had little knowledge of Sanskrit or even the Nagari script.

Professional Life

Chaudhuri tells us that he was over-ambitious as an undergraduate. In his B.A. history honours, he was placed first in the order of merit in the first class. However, he took on a vast reading list for his M.A and failed to pass his M.A. examination. I found this failure to be remarkable. How can someone who topped his university in his B.A. exam fail to clear his M.A.?

After his college education came to an end, Chaudhuri started to work for the Military Account Department. Initially he liked his job and won a lot of praise from his bosses, but he got bored and quit. Chaudhuri doesn’t tell us much about his career as a journalist or as a secretary to Sarat Chandra Bose, one can get these details from Wikipedia.

Chaudhuri was fascinated by military technology, he actually calls himself an expert on certain military matters and there are random references to publishing articles on military subjects. For example, while talking of a meeting with Pandit Nehru in 1931, to whom he was introduced by a friend, Chaudhuri says that he summoned courage to appear before Pandit Nehru on the strength of his articles on military subjects and the self-confidence he had acquired thereby. Having read the entire Autobiography, I can’t imagine Chaudhuri feeling nervous about meeting Nehru in 1931 when Nehru was not such a tall person. I assume Chaudhuri is merely being modest, just as he is when describing his apparent lack of felicity with the English language.

How did Chaudhuri become a military and weapons expert? We are told that he made a study of Napoleon’s Italian campaign. He followed the Russo-Japanese war, the Turco Italian War and the World Wars. From studying military history, he started to study the technical aspect of warfare and tried to learn the elements of gunnery and aviation. He developed a special interest in the breech mechanism of guns and understood them all. The only breech Chaudhuri failed to master was that of the Nordenfelt automatic. For some reason, I am not convinced that a man can become a technical expert on guns and the like by reading books on them.

Wikipedia tells me that Chaudhuri was a reasonably successful journalist, but there is little mention of his journalistic life in the Autobiography. According to this article, Chaudhuri was associated with Subhas Chandra Bose, but the Autobiography does not have much to say about Netaji.

On The Freedom Movement

Apparently during the civil disobedience movement of 1930, Chaudhuri was a passionate supporter of Gandhian methods. However, in the late thirties, he moved away from what he calls ‘Gandhism ideology’. I assume his disillusionment was the result of the knowledge he gained of the inner workings of the freedom movement, when he was secretary to Sarat Chandra Bose.

India's Weather - A Graveyard for Conquerors

Chaudhuri places some of the blame for India’s lack of vitality on the weather. According to Chaudhuri, so far no foreigner, Aryan, Turk or Anglo-Saxon, has been able to escape the consequences of living in the Indo-Gangetic plain, which he calls a Vampire of geography, with its high temperatures that sap human beings of all energy. As long as the peoples or civilizations which came into India remained vigorous in their native homelands and were able to reinforce themselves periodically, all went well. As soon as the source became weak or exhausted, political regimes and cultures set up in India by the conquerors went into decay.

Predictions

Chaudhuri calls on his readers to expect the appearance of an Indo-English equivalent of Indo-Persian Urdu after the disappearance of British rule, just as Urdu made its appearance with the decline of Moghul power. I’m not sure if this will come true, Hinglish notwithstanding, since the internet and television have brought Hollywood into our homes.

Of the three historical civilisations that have arisen so far in India – the Indo-Aryan, the Indo-Islamic and the Indo-European – by far the most original and massive was the first. Indo-Islamic was on a lower plane. The Indo-European civilisation was the least sturdy. However Chaurhuri expects the United States singly or a combination of the United States and the British Commonwealth to re-establish and rejuvenate the foreign domination of India.

The United States will beat the Soviets, we are told and I nod my head sagely.

What Made Him Tick?

As I came to the end of this 580-odd pages tome, I asked myself, what sort of man was Nirad C. Chaudhuri? One is offered a clue by Chaudhuri himself when he describes (somewhere in the middle of the book) how he was a fond of a neighbour, a young man named Devendra who told him stories and played with him. After some time, Devendra died of an illness. Those who attended Devendra’s cremation later told Chaudhuri that Devendra’s spleen had grown so large and hard that when the fire touched it, the thing shot off the pyre and had to be picked up from a distance, put back in the fire and kept in place with a pole. On hearing this, young Chaudhuri began to tear his hair and gnash his teeth, upset at not going to the cremation and seeing Cousin Devendra’s spleen bounding away like a red football and being picked up again. As you would have gathered, Chaudhuri was not upset at Devendra’s death, though he was fond of Devendra. Rather, he was upset that he could not see Devendra’s spleen bound away like a red football and get picked up again.

To conclude, one can say that Chaudhuri’s attitude towards India, Hinduism, Bengali society and Islam, as portrayed in the Autobiography, is one of curiosity mixed with a determination to not to allow his analysis to be affected by his personal affiliations, though he never disowns his religion or culture or language. Chaudhuri doesn’t mention caste at all and I assume he was proud of his caste. Ambedkar does not find any mention in the Autobiography either. In his later life, Chaudhuri is said to have justified the demolition of the Babri Masjid saying that the Muslims had no cause to complain for the loss of one Masjid when they had destroyed thousands of temples in the course of a thousand years. However, in the Autobiography, he maintains a stiff upper-lip and is a pucca neutral gentleman.

Modesty from a Non-Native English Speaker

Chaudhuri is quite modest as he sets sail. He announces very early on that he has no illusions about his mastery over the English language. ‘An author whose English was not learnt from Englishmen or in any English speaking country’, he describes himself, though it is clear that his writing does not have any reason to be shy. By the time Chaudhuri adds a bit later that he has never lived outside India, I am convinced that I am reading a master of the English language, possibly the best Indian English writing I’ve ever read, better than even Vikram Seth’s. Since Chaudhuri was around 50 when he published Autobiography of an Unknown Indian, the only other conclusion I can draw is that Chaudhuri did not come from a privileged background, something borne out from his disclosures in the rest of the book.

Brutally Candid

If you are a successful sports star or a politician or a businessman, writing an autobiography should be a straight forward, how-did-I-achieve-success narrative. Writers on the other hand, maybe because success as a writer is as much a function of the writer’s mental makeup and past trauma as it a result of hard work and persistence, make a virtue of excoriating themselves in public. JM Coetzee’s auto-biographical novel Summertime: Scenes from Provincial Life comes to mind. V. S. Naipaul arranged for sufficient personal detail to be provided to his official biographer Patrick French to write some pretty interesting stuff. If JM Coetzee strips himself bare and shines an unflattering light on his naked body in Summertime, Chaudhuri does the same for his community and country, without dissociating himself from either.

Family

Chaudhuri starts off by giving a detailed description of his parents and other family members. We are told that his father was a successful lawyer and the Vice-Chairman of the Kishorganj municipality. Those days, there were two categories of lawyers, Ukils with higher academic and professional qualifications and Muktears who largely handled criminal cases. Chaudhuri’s father was Muktear who made enough money to buy unlimited quantities of books for his children, who unusually for his time (and even by modern day standards) thought that education was an end by itself. The Chaudhuri children evidently grew up in a literary environment. One can’t help but be impressed when Chaudhuri says that he cannot remember the time when he did not know the names of Queen Victoria, Prince Albert, Napoleon, Shakespeare and Raphael. I think I heard of Raphael when I was 21! ‘The next series comprising Milton, Burke, Warren Hastings, Wellington, King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra is almost as nebulous in origin. Lord Roberts, Lord Kitchener, General Buller, Lord Methuen, Botha and Cronje, entered early thanks to the Boer war. Next in order came Mr. Gladstone, Lord Rosebery, Martin Luther, Julius Caesar and Osman Pasha (the defender of Plevna in the Russo-Turkish War of 1877-78) – these too belonging to the proto-memoric age. The beginnings of true memory in my case were marked by the names of Fox and Pitt, and Mirabeau, Robespierre, Danton, Marat, Junot (Napoleon’s marshal) and also perhaps Georve Washington. On the literary side, in addition to the names of Shakespeare and Milton which we imbibed unconsciously, we came to know of Homer as soon as we began to read the Ramayana and Mahabharata, which was fairly easy.’

When the family moved to Kolkata, Chaudhuri found school life to be a disappointment. However, the wider literary life in Calcutta was more lively and generous.

Rooted to the Bangla Soil

Even as he taught them English, Chaudhuri’s father made sure his children did not neglect Bangla literature. Chaudhuri takes us on a tour of the Bengali literary world, introducing us to its litterateurs of his time in the process. He starts with Michael Madhusudan Dutt, a wealthy Bengali who converted to Christianity. Chaudhuri calls him the greatest exponent and greatest martyr of Bengali humanism and a great scholar. We meet Bankim Chandra Chatterji who was, according to Chaudhuri, positively and fiercely anti-Muslim, the creator of Hindu nationalism. These men were not, in their days, darlings of the masses. We are told that Rammohun Roy and Tagore were underrated, ridiculed, slandered and even persecuted in a manner wholly undeserved and unexpected. Even a Hindu conservative like Bankim Chandra Chatterji was not fully understood by the masses. Vivekananda became a hero only after the Parliament of Religions at Chicago gave him an unexpectedly favourable reception. Most funnily, I learnt that Tagore's Bangla was not considered to be chaste or classy enough by many and this perception did not change until he won the Nobel!

Chaudhuri talks of Brahmo Samaj as an organisation whose morality was derived from puritan Christianity. It led a moral crusade attacking four vices namely sensuality, drunkenness, dishonesty and falsehood. Chaudhuri tells us that none of these vices had reached diabolic proportions, since feebleness and passivity permeated even the vices. Chaudhuri was evidently not a follower of the Brahmo Samaj.

On Calcutta and Bengalis

Even in those days, Calcutta was not a very clean city. Apparently Bengalis washed themselves and their clothes more than was necessary and tonnes of washing was always hung out to dry and garbage was dumped on roads. To slip on a mango or banana skin and have a sprained ankle was a very common mishap in Calcutta, we are told.

Elysium Row was a dreaded street since it had, Number Fourteen, the Headquarters of the special police or the political police. Apparently there were few Bengali young men with any stuff in them who did not have dossiers in Number Fourteen, and many had to go there in person to be questioned or tortured, or to be sent off to a detention camp.

Bengalis were very superstitious. For example, men tied up their hair in a knot before going to a WC since WCs were believed to be the favourite haunts of evil spirits who would possess them unless their hair was tied up. Cow dung was sprinkled liberally to purify things. Elderly women sometimes went nude when working in the kitchen since their clothes would otherwise be contaminated by food. The common man was opposed to all sorts of reform or to the emancipation of women. The sternest denouncers of Rammohun Roy or Tagore were the gentry of Calcutta.

Mixed Feelings Towards The British

Though Chaudhuri is supposed to be an anglophile, his feelings towards the British, which he conflates with that of Indians in general, are definitely mixed. According to Chaudhuri, during the Boer War, one-half of India automatically shared in the English triumph, while the other and the patriotic half wanted the enemies of England to win. Indians gloated over allied reverses and glory in German victories in both World Wars. This was done less openly in 1914 than in 1939.

Once when attending a concert in Calcutta with an English friend, sitting in the gallery, Chaudhuri saw row upon row of Englishmen and Englishwomen in graceful evening dress below him and there were no Indians. The thought of dropping a bomb on the crowd below came to Chaudhuri in his heated and excited state.

As a student, Chaudhuri too defaced pictures of Moghul emperors and English governor Generals. Even when they wrote of the Black Hole as a tragedy and the battle of Chillianwallah as a draw, in exam papers, they were convinced all the while that the former was a myth and the second a defeat for the English.

Once Chaudhuri and his brothers visited a battleship which had come to Kolkata. He was disgusted by the way Indian crowds behaved and Indian constables (under English sergeants) treated them. The crowds followed no queue or rules and swarmed all over. The police used batons, lathis and whips freely on the crowds. Apparently, that spectacle repeated was year after year on the visit of ships of the East Indies Squadron. Chaudhuri tells us that the ‘display of racial discrimination not surpassed in all the squalid history of Indo-British personal relations. The arrogance and absence of consideration shown by one side was matched only by the indiscipline and lack of self-respect shown by the other.’

Outright or fulsome praise for the British Empire is entirely missing in Autobiography of an Unknown Indian. One gets the feeling that Chaudhuri not only admired the British Empire and its achievements, he also envied them in the position of one colonised. Where there is praise, it is faint and even disguised. For example, when discussing the education system devised for India by the British, he says that ‘the educational system of British India has been accused of being only a machine for turning out clerks and officials. That certainly is true if we test the system by the use which was made of it in average instances and judge it by its average product. But it is not true if we take into account the intention of those who created the system. Many passed through the British Indian educational system mechanically, their approach akin to that of a man with a gun who uses it as a cudgel.’

Chaudhuri had no contact with English social life in Calcutta. Those were days of racial privileges and certain parts of Eden Gardens were roped off. Chaudhuri never went close to the English for he did not wish to invite rebuffs, he tells us.

Attitude Towards Muslims

Chaudhuri tells us that they learnt nothing of Islamic culture, although it was the spiritual and intellectual heritage of nearly half the population of Bengal and living in East Bengal, they came into intimate and daily contact with Muslims. Creators of modern Indian culture in the 19th century completely ignored the Muslims. After the end of Muslim rule, Hindu society had completely broken with Islam. ‘There was retrospective hostility towards Muslims for their one-time domination of the us. Even before we could read, we had been told that the Muslims had once ruled and oppressed us, that they had spread their religion in India, with the Koran in one hand and the sword in the other, that the Muslim rulers had abducted our women, destroyed our temples, polluted our sacred places. In nineteenth century Bengali literature, the Muslims were always referred to under the contemptuous epithet of Yavana.’

Despite doing his best to be neutral towards Muslims and Islam, Chaudhuri mentions an incident from school when Muslim students protested against acting certain scenes from a Bengali drama for the school anniversary day. Whilst admitting that the scenes were indeed offensive towards Muslims, Chaudhuri says that he went home in tears.

Chaudhuri’s views towards Muslims were influenced by his uncle Anukul who was in turn influenced by Bepin Chandra Pal. Ankul took the view that Pan Islamism was the greatest danger facing Indian nationalism. Chaudhuri agrees and for this reason, during the Turco Italian War and the two Balkan Wars when most Indians pro-Turkey, Chaudhuri was anti-Turkey.

On India’s Defeat By Islamic Invaders

Chaudhuri delves into the Hindu psyche in detail as he seeks to understand how Muslim rulers managed to conquer India and control the majority Hindus for so long. Chaudhuri says that Muslim rulers, as long as they remained strong, had no Hindu rebellion to fear. Provided they paid a commensurate reward they could count on being able to enlist any number of Hindus to act as administrators, army commanders, suppliers and advisors. Hindus would even advise them of the best means of bring other Hindus under subjugation. However, Hindu homes and kitchens were out of bounds for Muslims even as Hindu society tightened rules against intermarriage and commensality during the period of Muslim rule. Chaudhuri quotes Sarat Chandra Chatterji who summed by the underlying principle of Hindu behaviour with the example of a woman who has a low caste paramour and who boasts that although she has lived with him for twenty years, she had not, for a single day, allowed him to enter her kitchen.

According to Chaudhuri, India was a colonial empire of Islam. Unlike Persia which was conquered by Islam during its formative years, India was conquered after the Islamic order was fully grown and fully self-conscious. Chaudhuri refutes the argument that Islam declined in India because of Aurangazib’s (sic) intolerance. There were other Muslim monarchs who were less tolerant of Hinduism. ‘An Islamic society stretching from the Atlantic to the Oxus was not founded on the basis of perfect equality between the conqueror and the unconverted conquered. If an empire is founded as well as destroyed by intolerance, the intolerance ceases to have any causal significance for any part of the process. Tolerance or no tolerance, Indian Hindus were never reconciled to Muslim rule. The empire ceased to receive new administrators and soldiers from Iran and Turkestan and the resident Muslims were too denigrate.’ In short, the decline of the Moghul Empire was not due to uprisings by the Marathas or the Rajputs. Globally Islam had declined and this decline took India in its stride. ‘The revolt of the internal proletariat against Muslim rule was only the ass’s kicking of the sick lion.’

Weaknesses of Hinduism

Chaudhuri ticks off various Hindu weaknesses one by one, even as he does not even try to disassociate himself from his community. He gives the example of a contractor whose cow was strangled accidentally. The contractor was forced to wear sackcloth, drink half a glass of bovine urine and fast for a day. For the next three days, he lived and slept in the open on the spot where the cow had died and also abstained from eating anything but plain rice without even salt. He had to beg for alms, bellowing like an ox. Later he was sprinkled with cow urine even as all Brahmins of the locality were fed and the priests amply rewarded.

Chaudhuri says that the ethical immaturity of Hindu society is apparent from its failure to develop a sense of personal moral responsibility. ‘Taking of bribes, not giving value for money in public services is sanctioned or condoned by habit or custom. The doctrine of karma has dulled the Hindu’s conscience by entrusting the ship of morality to a sort of gyropilot,’ Chaudhuri says.As for Hindus who boast of the greatness of their heritage without much knowledge, Chaudhuri has only contempt. We are told that many Hindus from Punjab spoke of the greatness of Hindu culture and religion without being able to read not only Sanskrit but even Hindi. Colleagues who chided Chaudhuri for his fondness for English and French had little knowledge of Sanskrit or even the Nagari script.

Professional Life

Chaudhuri tells us that he was over-ambitious as an undergraduate. In his B.A. history honours, he was placed first in the order of merit in the first class. However, he took on a vast reading list for his M.A and failed to pass his M.A. examination. I found this failure to be remarkable. How can someone who topped his university in his B.A. exam fail to clear his M.A.?

After his college education came to an end, Chaudhuri started to work for the Military Account Department. Initially he liked his job and won a lot of praise from his bosses, but he got bored and quit. Chaudhuri doesn’t tell us much about his career as a journalist or as a secretary to Sarat Chandra Bose, one can get these details from Wikipedia.

Chaudhuri was fascinated by military technology, he actually calls himself an expert on certain military matters and there are random references to publishing articles on military subjects. For example, while talking of a meeting with Pandit Nehru in 1931, to whom he was introduced by a friend, Chaudhuri says that he summoned courage to appear before Pandit Nehru on the strength of his articles on military subjects and the self-confidence he had acquired thereby. Having read the entire Autobiography, I can’t imagine Chaudhuri feeling nervous about meeting Nehru in 1931 when Nehru was not such a tall person. I assume Chaudhuri is merely being modest, just as he is when describing his apparent lack of felicity with the English language.

How did Chaudhuri become a military and weapons expert? We are told that he made a study of Napoleon’s Italian campaign. He followed the Russo-Japanese war, the Turco Italian War and the World Wars. From studying military history, he started to study the technical aspect of warfare and tried to learn the elements of gunnery and aviation. He developed a special interest in the breech mechanism of guns and understood them all. The only breech Chaudhuri failed to master was that of the Nordenfelt automatic. For some reason, I am not convinced that a man can become a technical expert on guns and the like by reading books on them.

Wikipedia tells me that Chaudhuri was a reasonably successful journalist, but there is little mention of his journalistic life in the Autobiography. According to this article, Chaudhuri was associated with Subhas Chandra Bose, but the Autobiography does not have much to say about Netaji.

On The Freedom Movement

Apparently during the civil disobedience movement of 1930, Chaudhuri was a passionate supporter of Gandhian methods. However, in the late thirties, he moved away from what he calls ‘Gandhism ideology’. I assume his disillusionment was the result of the knowledge he gained of the inner workings of the freedom movement, when he was secretary to Sarat Chandra Bose.

India's Weather - A Graveyard for Conquerors

Chaudhuri places some of the blame for India’s lack of vitality on the weather. According to Chaudhuri, so far no foreigner, Aryan, Turk or Anglo-Saxon, has been able to escape the consequences of living in the Indo-Gangetic plain, which he calls a Vampire of geography, with its high temperatures that sap human beings of all energy. As long as the peoples or civilizations which came into India remained vigorous in their native homelands and were able to reinforce themselves periodically, all went well. As soon as the source became weak or exhausted, political regimes and cultures set up in India by the conquerors went into decay.

Predictions

Chaudhuri calls on his readers to expect the appearance of an Indo-English equivalent of Indo-Persian Urdu after the disappearance of British rule, just as Urdu made its appearance with the decline of Moghul power. I’m not sure if this will come true, Hinglish notwithstanding, since the internet and television have brought Hollywood into our homes.

Of the three historical civilisations that have arisen so far in India – the Indo-Aryan, the Indo-Islamic and the Indo-European – by far the most original and massive was the first. Indo-Islamic was on a lower plane. The Indo-European civilisation was the least sturdy. However Chaurhuri expects the United States singly or a combination of the United States and the British Commonwealth to re-establish and rejuvenate the foreign domination of India.

The United States will beat the Soviets, we are told and I nod my head sagely.

What Made Him Tick?

As I came to the end of this 580-odd pages tome, I asked myself, what sort of man was Nirad C. Chaudhuri? One is offered a clue by Chaudhuri himself when he describes (somewhere in the middle of the book) how he was a fond of a neighbour, a young man named Devendra who told him stories and played with him. After some time, Devendra died of an illness. Those who attended Devendra’s cremation later told Chaudhuri that Devendra’s spleen had grown so large and hard that when the fire touched it, the thing shot off the pyre and had to be picked up from a distance, put back in the fire and kept in place with a pole. On hearing this, young Chaudhuri began to tear his hair and gnash his teeth, upset at not going to the cremation and seeing Cousin Devendra’s spleen bounding away like a red football and being picked up again. As you would have gathered, Chaudhuri was not upset at Devendra’s death, though he was fond of Devendra. Rather, he was upset that he could not see Devendra’s spleen bound away like a red football and get picked up again.

To conclude, one can say that Chaudhuri’s attitude towards India, Hinduism, Bengali society and Islam, as portrayed in the Autobiography, is one of curiosity mixed with a determination to not to allow his analysis to be affected by his personal affiliations, though he never disowns his religion or culture or language. Chaudhuri doesn’t mention caste at all and I assume he was proud of his caste. Ambedkar does not find any mention in the Autobiography either. In his later life, Chaudhuri is said to have justified the demolition of the Babri Masjid saying that the Muslims had no cause to complain for the loss of one Masjid when they had destroyed thousands of temples in the course of a thousand years. However, in the Autobiography, he maintains a stiff upper-lip and is a pucca neutral gentleman.

Friday, 2 October 2015

Book Review: Making India Awesome, by Chetan Bhagat

Chetan Bhagat’s latest offering Making India Awesome is a work of non-fiction, a bunch of essays addressed to Indians who care and want to make a difference. Bhagat tells us that 80% of Indians don’t care about politics or government. Within the balance 20%, 80% are permanently aligned with a side, say with Modi or the Congress Party and will never criticise their side. Therefore, Bhagat’s essays are addressed towards the 20% within the 20% who are non-aligned and care. Bhagat calls them “Caring Objective Indians”. What comes out indirectly is that Bhagat is also not allied with any person or party – some of his essays criticise the BJP and some the Congress.

I agree with a number of Bhagat’s homilies. He is all for gay rights and empowering women. He wants men to support their wives’ careers’ the way Mary Kom’s husband Onler Kom has done. He has seventeen commandments for Modi and I agree with each of them. In a second essay on Modi, one analysing the "Modi effect", Bhagat says that Modi’s success is largely due to luck, since he only had to deal with the not-so-smart or effective Rahul Gandhi. BCCL’s monopoly and stranglehold over Indian cricket is questioned. Bhagat opposes the ban on porn and alcohol and wants Indians to watch their diet and eat less junk food.

Bhagat has a number of pieces addressed to Indian Muslims and though Bhagat simplifies issues, on the whole his advice is sound. Similarly, there are a number of articles addressed to women. I am not sure they’ll all go down so well, but I am convinced that Bhagat means well.

The best of the lot in Making India Awesome are two chapters on admissions to Delhi University (which could apply to any other prestigious college’s admission process) and the pressure to score high marks. Bhagat speaks from the heart and makes very valid points.

I do not agree when Bhagat says that the creation of Telangana was a mistake and that it does not make sense to break up states into more efficient administrative units. In fact, there is a very potent argument that it is time to restructure India into smaller states.

However, as usual, Bhagat refuses to revolt or stick his next out. In one essay he cribs about how a VIP, a Minister’s convoy held up traffic and nearly caused him to miss a flight. He does not name and shame that VIP. When advising the Congress, Bhagat asks them to weed out party members who are old, rusted and tarnished. I have some sympathy for Bhagat’s demand for young politicians, but even ignoring his beef against “old”, I wonder why Bhagat can’t name the Congress politicians he wants to be weeded out. Did he mean Sharad Pawar? Is he scared of taking names? Funnily, Bhagat tells us that India’s bureaucrats understand the system well and can fix the system, but according to Bhagat, Indian babu’s don’t have “guts”!

Bhagat also does not spell out things when he could. He wants the economy to be opened up and controls removed. What does he mean by this? Most controls on foreign investments are based on the principle that India is not ready for full capital account convertibility (the ability to convert Indian assets and currency into foreign assets or currency and to take them out of India without the need for the RBI's approval). Does Bhagat want India to permit foreigners to invest in Indian real estate without restrictions (which may drive up prices even higher?). On this aspect, I expected something much better from Bhagat – after all, he is a former banker!

Bhagat manages to discuss Godhra without offending or blaming anyone or adding any value.

On India’s northeast, he says that every time one visits the Northeast, the locals beg us for attention and to be treated as Indians. ‘The Northeastern people are beautiful and attractive. They also have slightly different, more oriental physical features as compared to the rest of us.’ Trust Bhagat to make matters simple. Isn’t Bhagat aware that there are a number of places in the Northeast where the people don’t think they are Indians, where plains people aren’t welcome? As for racism, surely it’s a two-way street? Just as many Indians think the North-easterners are different, many in the North East think Indians are too dark and different. Many parts of the Northeast have resisted integration with independent India because historically they have had very little to do with what’s now called India and because they are very different in terms of looks and culture.

When arguing for the replacement of Devnagri with the Roman script, Bhagat calls himself a Hindi lover. Yes, we were recently educated on that point by noted lyricist Gulzar, weren't we? Sorry, I’m being cheap and at the risk of digressing, let me say that as an emcee, Bhagat was only doing his job when he said something nice about Gulzar’s poetry. If in the midst of a headache, I respond with a “I’m fine” to your “How do you do?”, I does not mean I am a liar. It merely means I do not want to share my personal details (my headache) with you at that point in time. You get what I mean. I’m totally with Bhagat on this one. For the record, my Hindi is really atrocious and I've been trying to improve it with Bhagat's help.

Kashmir is conspicuous by its absence. In his What Young India Wants, Bhagat had advocated negotiating with Pakistan over Kashmir, even going to the extent of suggesting that India be prepared to make compromises.

On the whole, Bhagat writes in simple English, which is grammatically correct. No, it is not beautiful or lyrical prose, but it is easy to read.

As I read Making India Awesome, I had this nagging feeling that some of it was familiar stuff and that I may have read these thoughts earlier. Was Bhagat plagiarising from someone else’s work I wondered and turned to the internet. What did I find? No, there’s no plagiarism and that’s because all the essays in Making India Awesome (except for one titled We The Shameless, which has been entirely re-written) are articles previously published on Bhagat’s own blog and are still available on-line. For this reason, the articles relating to Indian Muslims and women’s rights have a lot of overlap. In fact, two of the articles relating to women’s rights start off with a reference to the Bollywood movie ‘Cocktail’.

Hear, hear, all you Chetan Bhagat fans out there. You need not buy Making India Awesome. Instead, you can, if you wish, re-read his old articles on his blog. Below you’ll find the list of articles from Bhagat’s blog which have been compiled, with minor modifications, to create Making India Awesome. Of course, the introduction and conclusion are previously unpublished pieces. I do wish Bhagat’s publishers had disclosed upfront that Making India Awesome is almost entirely composed of previously published articles.

AWESOME GOVERNANCE: POLITICS AND ECONOMY

POLITICS

Seventeen Commandments for Narendra Modi

Games Politicians Play In The Silly Season Of Elections

Revenge of the Oppressed: Why corruption continues to be around despite the outcry against it

The Kings in Our Minds

The Telangana effect

Analysing the Modi Effect

Can India’s Backward Polity Ever Provide A Pro-Growth Economic Environment?

Rahul’s New Clothes, And The Naked Truth

Swachh Congress Abhiyan In Four Essential Steps

Once Upon A Beehive

ECONOMY

Rescue the Nation

To Make ‘Make in India’ Happen, Delete Control

Pro-Poor Or Pro-Poverty?

The Tiny Bang Theory for setting off big-bang reforms

AWESOME SOCIETY: WHO WE ARE AS A PEOPLE AND WHAT WE NEED TO CHANGE

Time To Face Our Demons

We Have Let Them Down

Watching The Nautch Girls

Let’s Talk About Sex

The Real Dirty Picture

Saying Cheers in Gujarat

Our Fatal Attraction to Food

Cleanliness Begins at home

India-stupid and India-smart

Scripting change: Bhasha bachao, Roman Hindi apnao

Mangalyaan + unlucky Tuesdays

A Ray of Hope

Junk Food’s Siren Appeal

AWESOME EQUALITY: WOMEN’S RIGHTS, GAY RIGHTS AND MINORITY RIGHTS

WOMEN’S RIGHTS

Ladies, Stop Being so Hard on Yourself

Five Things Women Need To Change About Themselves

Home Truths on Career Wives

Wake Up And Respect Your Inner Queen

Indian Men Should Channelize Their Inner Mr Mary Kom

Fifty Shades Of Fair: Why Colour Gets Under Our Skin

GAY RIGHTS

Section 377 Is Our Collective Sin

MINORITY RIGHTS

Letter from an Indian Muslim Youth

Being Hindu Indian or Muslim Indian

It’s Not moderate Muslims’ fault

Mapping the Route To Minority Success

AWESOME RESOURCES: THE YOUTH

Open Letter to the Indian Change Seekers

We the Half Educated People

Du-ing It All Wrong, Getting It All Mixed up

How the Youth Can Get Their Due

Scored Low in Exams? Some Life Lessons From a 76 percenter

Tuesday, 29 September 2015

Book Review: Red Sorghum, by Mo Yan

Ever since Mo Yan won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2012, I’ve been planning to read Red Sorghum, one of his most famous works set in the time of the Japanese occupation and the Second World War. Since I knew that Mo Yan is a member of the Cultural Affairs Department of the People’s Liberation Army, I expected another Mikhail Sholokhov. I turned out to be totally wrong. Those who have read Sholokhov would know that Sholokhov paints good and bad (read that the good communists and the bad Czarists and petty bourgeois) in black and white. Mo Yan, on the other hand, at least in Red Sorghum, is a uniquely talented story teller who delights in portraying life in vivid contrasts, terrific joie de vivre suddenly being replaced by excruciating pain, delightful surprises being taken over by extreme sorrow. The setting for his novel, the Northeast Gaomi Township, is a place of extreme beauty, the land of sorghum, which the locals use to make wine. Sorghum is a life giver and entertainer – everyone in the Northeast Gaomi Township drinks sorghum wine. The narrator’s grandfather, Yu Zhan’ao, is a bandit who managed to marry Dai Fenglin, a pretty woman after killing her rich husband and father-in-law, all with her silent acquiescence. You see, Dai Fenglin’s husband had leprosy and her father had married her off to the leper just to get a black mule for himself. Yu Zhan’ao’s execution of the murders and his subsequent marriage to Dai Fenglin would not be out of place in a Bollywood blockbuster.

There are so many characters who are so exciting, so out of the ordinary that one feels a novel could have been written around each of them. There’s Arhat Liu, a man who loved his mules so much that he broke their legs, after they had been confiscated by the Japanese, and was skinned alive for his pains. There’s Nine Dreams Cao, an honest and upright magistrate who does not hesitate to use beatings to extract confessions and still does not always get it right. There’s Spotted Neck, a bandit whom Yu Zhan’ao admires and later kills. There’s Black Eye who heads the Iron Society, which believes in the power of black magic and whose soldiers charge at armed enemy soldiers chanting “Amalai” and achieve a certain degree of success, only to be mowed down later.

It’s not just the people who are so unique and interesting. The funerals one attends when reading the Red Sorghum are out of the world. In the midst of so much fighting and poverty, so much money and symbolism is invested in funerals. Dogs. I still can’t decide if Mo Yan likes or hates dogs. The narrator’s family keeps dogs, more as guard dogs than anything else. After a Japanese massacre when dead bodies are piled up on the outskirts of the Northeast Gaomi Township, dogs feast on the corpses. The narrator’s family go out of the way to chase the dogs away, using up most of their precious ammunition. The dogs on their part go back to their primitive traits and form gangs to eat the corpses and attack those trying to chase them away. The fighting is fierce and deadly and some humans die. The narrator’s father, Douguan, loses one of his balls. Toward the end when the Jiao Gao are desperately looking for a way to fight off hunger, cold and the Japanese, Pocky Chen suggests a way out, one which harnesses the dogs in the vicinity.

I always thought that a ride in a sedan chair carried by four bearers would be as comfortable as a ride can get. Oh no! For Mo Yan, the inside of the sedan, which carries Dai Fenglin to her husband’s home is like a coffin. The walls oozed grease and there were flies inside. The sedan bearers, when they want to have fun, tease the bride sitting inside and rock the sedan so violently that the bride throws up!

I’ve heard of feet binding practised in the China of yore, but I never really thought anyone would find a small foot (the result of many years of painful binding which cracks the bones and causes the toes to turn under) attractive. Mo Yan tells that the five feet four inch Dai Fenglin had toes which were three inch golden lotuses. When she walked, swinging her arms freely, her body swayed like a willow in the wind. When she was being carried in a sedan to her husband’s home, one of her tiny feet poked out of the sedan and the sight of that incomparably delicate, lovely thing nearly drove the soul out of the bearers’ bodies.

As I read Red Sorghum, I waited in vain for that rare reference to the Chinese Communist Party, which would show the Party as the defender of the common man and a force for good. I waited in vain. In the few confrontations between local Red guards and the poor farmers, the Reds don’t come out looking so good. There is a stray mention of the back-yard furnace campaign during the Great Leap Forward in 1958 which apparently resulted in the family’s wok being confiscated. Toward the end, the narrator visits Northeast Gaomi Township and finds that the place has been planted with hybrid Sorghum which he loathes. ‘Hybrid sorghum never seems to ripen, Its grey-green eyes seem never to be fully opened. I stand in front of Second Grandma’s grave and look out at those ugly bastards that occupy the domain of the red sorghum. They assume the name of sorghum, but are bereft of tall, straight stalks; they assume the name of sorghum, but are devoid of the dazzling sorghum colour. Lacking the soul and bearing of sorghum, they pollute the pure air of Northeast Gaomi Township with their dark, gloomy, ambiguous faces.’

Is hybrid sorghum used as a metaphor for change, I wondered? Is Mo Yan trying to suggest that the Communist Party has not made things better? After a great of thought, I have come to the conclusion that Mo Yan is not trying to say anything of that sort. Red sorghum has been replaced with hybrid sorghum. The narrator liked red sorghum. He does not like hybrid sorghum. Period.

Here’s an interesting article which suggests that writers like Mo Yan carefully criticise lower ranking Party officials once in a while, but never question those at the top, who are apparently unaware of the bad things that happen at the village level. Maybe that’s a fair comment, but Mo Yan is one helluva writer who, going by Red Sorghum, deserved the Nobel.

Monday, 7 September 2015

Learning Hindi With Chetan Bhagat

I’ve been trying to learn Hindi ever since my late teens. I learnt some Hindi at school, but a small dusty town down South is not the best place to learn the most widely spoken Indian language. As far as I can remember, I had a Learn Hindi In 30 Days with me for the entire five years I spent at law school in Bangalore. I made some progress, I could easily count up to hundred, but I could never bring myself to speak Hindi fluently.

After I moved to Mumbai, my comprehension skills improved tremendously, I could understand everything I heard, but I still couldn’t speak Hindi with any degree of fluency. My interest in learning Hindi waxed and waned, but the real reason I never learnt Hindi properly is that I couldn’t bring myself to watch either Bollywood movies or Hindi soaps. For someone who is otherwise surrounded by a non-Hindi speaking crowd, that’s fatal.

After 4 years in Mumbai, I went to the UK and didn't return for 8 years. I forgot almost everything when I came back.

Recently I re-kindled my interest in learning Hindi. I actually hired a teacher to take me through the basics once more, until I could read Hindi text with some speed. The problem was that my Hindi vocabulary is so very poor, I need to refer to a dictionary every two minutes to understand what I read.

In order to improve my vocabulary I tried a number of tricks. I would buy Hindi newspapers and read them. I tried reading schoolbooks, but Indian school books are essentially meant for children whose mother tongue is Hindi. Unlike English textbooks which seek to teach English as a foreign language, Hindi textbooks seem to assume that the learner can speak Hindi well.

I tried reading novels, but most Hindi novels have a lot of Sanskrit or Urdu words which aren’t in day-to-day usage. I wanted a novel written in the simple Hindustani spoken by the common man. It was then that I remembered Chetan Bhagat, the man who writes for the Common Man, in the Common Man’s English.

I have read all of Chetan Bhagat’s novels and have even reviewed some of his most recent works, such as Revolution 20/20, What Young India Wants and Half Girlfriend.